The reader who is coming to the subject of photography for the first time may find himself bewildered by the terminology used by the camera dealer down the street : the stops, shutter speeds, film development and the like. If you are planning to buy a box camera and are feeling confused and hopelessly at sea, this article should help dispel most of your doubts.

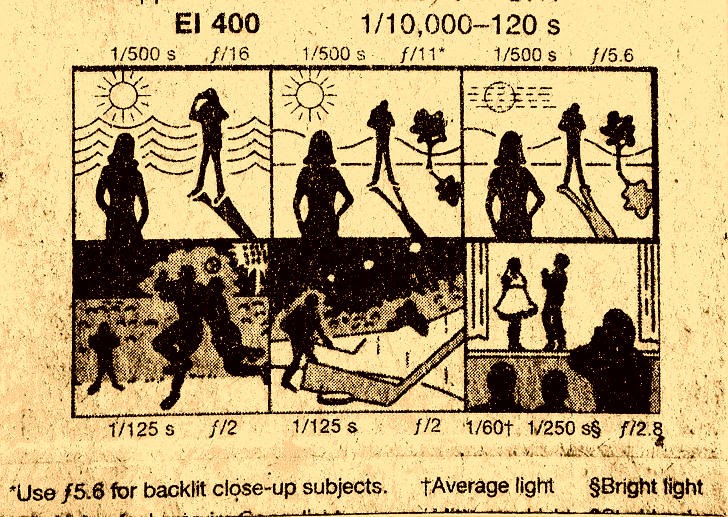

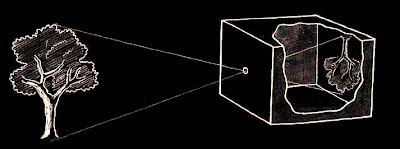

The

simplest kind of camera is a pin-hole camera. As the cut-out illustration here

shows, this is a light tight box with a tiny pin prick made on one side and a

sheet of film held at the other side. If the box is now aimed at an object,

rays of light coming from the scene criss-cross each other as they pass through

the pin-hole giving rise to a faint upside down image on the film.

The pin-hole camera is often looked upon as a mere scientific novelty, but actual photographs may be taken with the device, the only impediment being that as the image produced is exceedingly dim in illumination, the film or plate has to be exposed for a lengthy period running into several minutes.

|

| A pinhole camera forms an inverted picture of a scene, and forms the basis of the camera-obscura, the forerunner of the modern camera. |

The pin-hole camera is often looked upon as a mere scientific novelty, but actual photographs may be taken with the device, the only impediment being that as the image produced is exceedingly dim in illumination, the film or plate has to be exposed for a lengthy period running into several minutes.

A pin-hole

device can also be used as an object of amusement. For this purpose, the back

of the box which receives the film is replaced by a sheet of tracing paper or a

ground glass screen. If the box is now pointed at a brightly lit scene and the

user takes cover under a dark cloth or blanket, he will find a faint image

appears on the screen. If the picture is too faint to be viewed comfortably the

pin-hole may be enlarged. This gives a brighter result but increases the

fuzziness of the picture. For best results, a simple positive lens from the

optician’s shop held in a cylindrical cardboard tube may be substituted in

place of the pin-hole. With a bit of trial the lens can be focused when a

bright and clear picture will be seen on the screen. A device of this kind is

known as a camera obscura, and was used in the 17th and 18th centuries by artists to

trace perspective views of landscapes and architecture in paintings.

The camera

obscura with its bright, magical image was also used as a novelty in public

places in earlier times. People marvelled at the lifelike picture showing

branches swaying in the wind, people moving around, and architecture, but the

picture seen was only a fleeting impression leaving no permanent trace on the

wall or screen which received the impression.

The camera

obscura embodies within it the basic principle of the photographic camera, but

the arrival of photography had to wait till the mid-nineteenth century when

advances in applied chemistry made it possible to record the image permanently

on a chemically treated surface.

Photography

is thus the result of two distinct lines of scientific progress : optics, which

helps form an image of a scene on a flat surface, and chemistry, which produces

a permanent record of this image.

In 1851, a London sculptor named Scott Archer came up with a chemical process of photography known as the Wet Plate Process, which though far too cumbersome by present day standards, was nonetheless a great improvement on earlier processes in use (read more about this later). Archer's process remained in use until 1871, when Richard Leach Maddox came up with the idea of dry plates. A dry plate was a glass plate with a photographic light sensitive coating quite similar to the one we have on photo-film today, and the process, unlike Archer's method, made it possible to take camera exposures whilst the plates were dry. This innovation was to set an important milestone; it marked the beginning of modern photography, paving the way for further improvements in the line. It also led to the invention of flexible photographic film as we know it today. Once the

basic problems of the process were overcome inventors and designers turned their

attention to devising all kinds of innovative features aimed at making the camera a

versatile tool. In the early days of dry plates, a great number of detective spy cameras appeared, each tiny instrument promising a feature that made it remarkably easy to take pictures outdoors without drawing attention to itself. Among the camera models developed from the last decade of the nineteenth century onwards were the hand-held folding camera

using accordion style bellows designed so that the camera could be made to

collapse ; the twin-lens reflex and the single-lens reflex ; and the miniature,

a camera so unobtrusive it made possible for the first time true candid shots

of everyday scenes. Each of these designs was highly sophisticated and gave

splendid performance in the field for which it was intended, but the knobs and

dials on these instruments also meant that amateurs generally tended to look upon

photography as an impossibly difficult pastime requiring specialized knowledge.

The box camera, first introduced by George Eastman in 1888, overcame this

difficulty by presenting the amateur with an instrument simple enough to operate

and having the minimum of adjustments, thus bringing photography within the

scope of the average layman who had no knowledge of the subject.

With this background information in hand, we are in a position now to take a closer look at the inside of a box camera. No matter

how complicated it may seem, every film camera is made up of a light tight box

with a lens at one end whose purpose is to project a clear, well-defined image

of the scene being photographed onto a light sensitive film held flat at the

other end.

The figure

here shows a simplified view of the interior of a box-type camera. These

cameras typically used ‘roll film’, available earlier in a variety of sizes. As

you can see, the loaded spool is held at the bottom of the box and after each

picture is snapped a film wind knob or key is turned to bring fresh unexposed

film over the picture area in readiness for the next picture.

Many box cameras employ a simple meniscus (or spectacle type) lens to form the picture on the film. Working on its own, a simple lens of this kind gives a fuzzy image, and the manufacturer gets round this trouble by having a thin metal plate next to the lens with a tiny hole punched in it. This plate, known as a ‘stop’ blocks off all extraneous light rays coming from the subject letting only a narrow central beam to get across resulting in a picture that is sharp and well defined over its whole area.

|

| The interior of a box camera. Note that the film carrier which holds the spools is omitted. |

Many box cameras employ a simple meniscus (or spectacle type) lens to form the picture on the film. Working on its own, a simple lens of this kind gives a fuzzy image, and the manufacturer gets round this trouble by having a thin metal plate next to the lens with a tiny hole punched in it. This plate, known as a ‘stop’ blocks off all extraneous light rays coming from the subject letting only a narrow central beam to get across resulting in a picture that is sharp and well defined over its whole area.

Working

close to the stop is another mechanical contrivance that is known as the

shutter. In a box camera the shutter may consist of a spring-driven plate which

in its normal state covers the lens opening in the stop thereby allowing no

light to reach the film. When you press the button to snap a picture, the

shutter blade smartly flips aside flashing the picture on the film briefly

(usually 1/25 second) before it moves back into place to cover the lens opening

again.

The

shutter therefore decides the duration of time light acts on the film when you

take the picture. The stop on the other hand governs the brightness of the

image momentarily flashed on the film—the tinier the lens opening, the fainter

the picture flashed. Between them, these two components govern the total quantity

of light reaching your film during picture taking.

If you

pick up a professional camera like a single lens reflex, you will find that it carries a number of dials and levers with numbers printed alongside.

These cameras being sophisticated are provided with expensive lenses with a

stop whose opening can be varied within wide limits, and likewise the shutter is an intricate mechanism giving a range of exposure times. The beginner when asked to take a picture

with such a camera may find it requires a good deal of mental gymnastics to

select the lens opening and shutter time that will lead to a successful

picture. He will find that he is better off with a box camera which requires

very little thinking on his part. The camera manufacturer is aware of this

difficulty and he simplifies his box by having a single lens opening and a fixed

exposure time, so chosen that a picture taken outdoors in bright sunshine comes

out with perfect success. A box camera is therefore a fair weather camera,

although several models were made with 2, even 3 different lens openings which

allowed pictures to be taken outdoors even when it was dull and cloudy.

But to return to our illustration, the lens shown here is set in the body of the camera with no adjustment for focussing. This may appear strange, but it is yet another way the designer simplifies the operation of his camera. A lens of this kind is known as a fixed focus lens ; it is set during manufacture to give sharp pictures of distant objects. As the stop opening used on these cameras is only the tiniest hole about a few millimeters wide, objects even as close as 7 or 8 feet away from the camera begin to pose as ‘distant’ for the lens. This means that everything about 8 feet away and beyond will appear with equal sharpness on the film, a feature welcomed by most amateurs as it frees them from the worry of focussing while snapping their pictures.

But to return to our illustration, the lens shown here is set in the body of the camera with no adjustment for focussing. This may appear strange, but it is yet another way the designer simplifies the operation of his camera. A lens of this kind is known as a fixed focus lens ; it is set during manufacture to give sharp pictures of distant objects. As the stop opening used on these cameras is only the tiniest hole about a few millimeters wide, objects even as close as 7 or 8 feet away from the camera begin to pose as ‘distant’ for the lens. This means that everything about 8 feet away and beyond will appear with equal sharpness on the film, a feature welcomed by most amateurs as it frees them from the worry of focussing while snapping their pictures.

Having now

seen the interior of a box camera, let us now suppose we actually load our box

with a film and try our hand at taking a few pictures outdoors. Roll films, as

your photo dealer will show you, come in a variety of ‘speeds’. The speed of a film

is measure of its sensitivity to light. Thus a film with ISO 50 marked on

the box has low sensitivity and is said to be a slow speed film. A speed

of ISO 100 or thereabouts is considered a medium speed film and is recommended

for general photography. On the other hand if the film box is marked ISO 400 or

so, it means it is a high speed film requiring only a very short burst of light

to register the image.

For most general photography, a medium speed film is all that is needed, so we load up our box with a roll of medium speed. Now as we go about snapping pictures, what actually happens within the camera is this : each time you click a picture, the lens projects on the

film an image of the scene in a short burst of light. Although no picture

appears at this stage, a chemical change has in fact occurred on the emulsion,

which is the light-sensitive coating on your film. An invisible picture known

as a latent image has been formed on the emulsion. Next, the film is removed

from the camera in total darkness and put through a solution known as the

developer which brings out the image. This is followed by another solution

known as a fixing bath which makes the picture a permanent record and keeps it

from fading away in time.

For most general photography, a medium speed film is all that is needed, so we load up our box with a roll of medium speed. Now as we go about snapping pictures, what actually happens within the camera is this : each time you click a picture, the lens projects on the

film an image of the scene in a short burst of light. Although no picture

appears at this stage, a chemical change has in fact occurred on the emulsion,

which is the light-sensitive coating on your film. An invisible picture known

as a latent image has been formed on the emulsion. Next, the film is removed

from the camera in total darkness and put through a solution known as the

developer which brings out the image. This is followed by another solution

known as a fixing bath which makes the picture a permanent record and keeps it

from fading away in time.

After the

film has been washed and dried it may be inspected by holding it up to the

light. The picture will be now clearly seen. It is a darkish record ; light

areas in the original scene appear dark, while dark areas are rendered white.

The image formed is thus reversed in tones and is known as a negative.

Having secured a record of the scene as a negative, the next step consists of laying the negative on a photographic paper and shining a light onto it. When the paper is processed in chemicals similar to those used in making the negative, a picture in life-like tones is produced.

Having secured a record of the scene as a negative, the next step consists of laying the negative on a photographic paper and shining a light onto it. When the paper is processed in chemicals similar to those used in making the negative, a picture in life-like tones is produced.

This is

only the beginning of our excursion of this fascinating subject. As you go

along, you will find more examples of work produced with a box camera. You will

also find interesting historical details as well as a full technical discussion

of the features of these cameras further on in this website.

Ravindra Bhalerao

Ravindra Bhalerao